When Virginia ended gerrymandering, one of the benefits touted was more competitive elections without the lopsided districts drawn to favor an incumbent. Perhaps not so widely anticipated is that the race for the new 11th District in the state Senate June 20 primary would pit two well-regarded incumbent Democrats vying to represent Charlottesville and Albemarle.

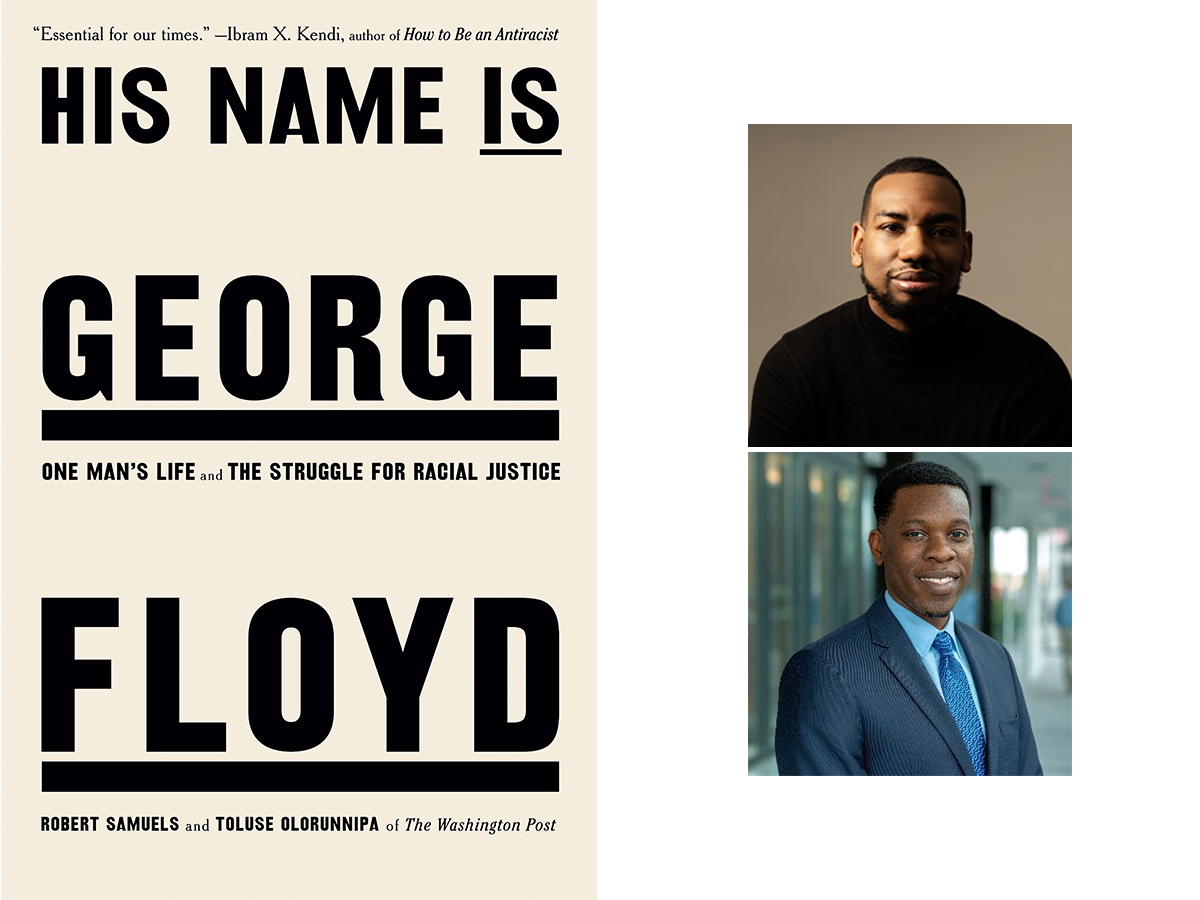

Senator Creigh Deeds, 65, a lawyer, has represented this area since 2001, when he won the 25th District seat previously held by Emily Couric. Delegate Sally Hudson, 34, an economics professor at UVA, has served two terms and was the first woman elected to represent Charlottesville in the 57th District in 2019.

The candidates, who share more Democratic ideals than not, have posed a quandary for some Dems. “I’m so confused,” says one city resident. “They’re both good candidates.”

J. Miles Coleman, associate editor for Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the Center for Politics, casts the race as “seniority for Deeds versus ideology with Hudson.” And he compares it to New York, if “[Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] challenged [Majority Leader] Chuck Schumer for Senate.”

At stake is control of the General Assembly under Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin, and all 140 seats are up for election. Dems narrowly control the state Senate with a 22-18 majority, while the GOP has a 52-48 majority in the House.

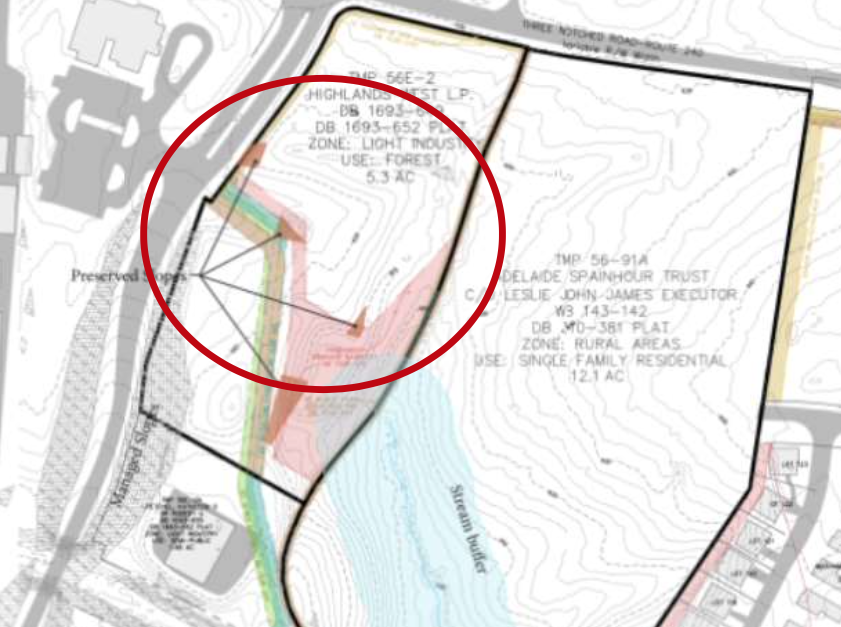

And it’s the first election in Virginia with an un-gerrymandered map after voters passed a constitutional amendment in 2020. That’s resulted in a wave of retirements in both chambers, including longtime Del. Rob Bell. Before, reliably blue Albemarle and Charlottesville were eviscerated into six General Assembly districts. Now the area has three districts, all facing competitive Democratic primaries.

The former 25th District stretched from Charlottesville to Bath County, from whence Deeds hails, at the West Virginia border. For years he carried bills to end gerrymandering, to no avail until the Democratic sweep of the legislature in 2019 under then-governor Ralph Northam. Like many incumbents, Deeds found himself no longer living in the district he’d represented. He moved to Charlottesville.

“I probably should have moved after my son died,” says Deeds. During a mental health crisis in 2014, Gus Deeds took his own life after attacking his father. “I lived in that house too long.”

“He moved here from almost two hours away,” says Hudson. Charlottesville “is one of the progressive strongholds on the state map, and I think the senator for Charlottesville has to be willing to push the pace of change in Richmond.”

“I’ve got a long record of getting things done,” says Deeds, who spent 10 years in the House of Delegates before winning the Senate seat. “[Virginia Public Access Project] says I get more bills passed than anyone else.”

Hudson says she wouldn’t have sought the state Senate seat without redistricting, which was her gateway to politics as a grassroots volunteer for the anti-gerrymandering organization OneVirginia2021. She stresses the significance of this “once-ever” election: “You only end gerrymandering once.”

Hudson has challenged an incumbent before, when she announced her House candidacy before David Toscano, then House minority leader, said he would not seek another term. And as in 2019, she brings cash from mega-donor Sonjia Smith and Smith’s hedge-funder husband Michael Bills’ Clean Virginia, which contributes to candidates who eschew Dominion Energy donations. Hudson also got a $20,000 check from top Berkshire Hathaway strategist Ted Weschler, who co-owns C-VILLE Weekly, according to VPAP.

Deeds also received a donation from Clean Virginia, as well as from best-selling author John Grisham and his wife Renee. He was sitting on more cash in the last filing period, with the largest segment of donations coming from fellow legislators and fellow lawyers, but Deeds pooh-poohs his cash advantage and suggests Hudson will receive more money after the filing deadline. Both candidates are running nonstop television ads.

Of the differences between Hudson and him, Deeds says it’s “probably more style than substance.” For example, they both mention they’ve been commended by abortion rights groups.

Hudson points to marriage equality, the death penalty, and gun safety as issues in which she thinks Deeds is out of step. “I think historically Senator Deeds has come around when the coast is clear, and I think the senator from Charlottesville has to be willing to stick their neck out before it’s safe,” she says.

“Silly” is how Deeds characterizes Hudson’s assessment, while he concedes that some of his positions have evolved over the decades. He supported Virginia’s 2006 constitutional amendment limiting marriage to between a man and a woman, citing his conservative Christian upbringing. “It’s an issue a lot of people evolved on, and I came around before Barack Obama,” he says.

Hudson says Deeds crossed party lines to repeal Virginia’s ban on purchasing more than one handgun a month in 2012, voted against a bill that would hold parents accountable for safely storing firearms, and voted against an assault weapons ban in 2020, “issues that are deeply important to this community.”

The assault weapons bill “was clearly overbroad, broader than federal legislation and would have included rifles,” says Deeds, who carried an assault weapons bill this year. “And I didn’t vote against it. I voted to send it to the crime commission for study.”

During her two terms, Hudson says she’s proudest of repealing restrictions on insurance coverage on abortion, fossil fuel subsidies, and the coal tax credit. She puts economic justice at the top of the list.

“I’m an economist by training so my focus is almost always on the financial challenges that are facing Virginia families,” she says, especially in “one of the most deeply unequal districts” in Virginia, where some of the wealthiest live, and Charlottesville, where 23 percent of its residents live below the poverty line.

“She brings a different expertise,” says former Charlottesville vice mayor Dede Smith. “She’s not a lawyer—and there are a lot of lawyers in the House and Senate. She’s a labor economist, and she deeply understands that sector and that need. She’s smart and she immediately grasps issues.”

Says Smith, “As a baby boomer, it is time to pass the baton to a younger generation that’s so much savvier about how to make change.” She adds, “We do need to recognize that policy and change will be felt more by the younger generation.”

Toscano, a Deeds supporter, sees Deeds’ seniority—if reelected he’ll be the number two Democrat in the Senate—as the way change will be made. Deeds co-chairs the Judiciary Committee, which appoints judges. He’s also on the powerful Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee, which determines what gets funded in the budget, including teachers’ salaries, educational funding, and mental health spending, the first person from this area to do so in decades.

“If Sally had run for the House, she would have easily won reelection and come into the body with a lot of seniority,” says Toscano. “If Creigh goes, this region loses all its seniority because Sally comes in at the bottom.”

Hudson maintains that seniority is no longer that big a deal in the House, where the Democratic caucus leader has four years experience like she does. It’s a culture change that’s “really healthy,” she says, and needs to be imported to the Senate.

Toscano calls Deeds a “progressive champion,” and wonders why voters would “throw someone out who has had such a great run and is in a position to do so much more.” Says Toscano, “I look at what Sally has to gain and what we have to lose. The biggest question is, ‘Why?’”

One of the issues Deeds says he’s not willing to walk away from is mental health reform. That’s a task he compares to “eating an elephant. You take a big bite, and feel like you’ve accomplished a lot. Then you look ahead and realize how much more there is to do.”

Both Deeds and Hudson see a dire situation if Republicans gain control of the Senate. “We could be looking at a six-week abortion ban,” says Deeds.

“I could see both chambers go either way,” says the Center for Politics’ Coleman.

He mentions a 2020 Massachusetts race in which Joe Kennedy challenged incumbent U.S. Senator Ed Markey—and lost. “There’s not much appetite to get rid of incumbents who didn’t have any obvious apostasies. Deeds hasn’t gone out of his way to antagonize the Democratic base.”

And even if Hudson loses, Coleman would not be surprised if she carries the city of Charlottesville.

Albemarle makes up the majority of the district, which includes Nelson, Amherst, and a slice of Louisa County. Predicts Toscano, “The race is going to be won or lost in Albemarle County.”

Toscano worries more about the money spent in this primary on two safe seats that could be used in other parts of the state to bolster Democrats.

“That’s not how fundraising works,” says Hudson. “The reality is that primaries pull more people into the process. Competitive elections engage people,” and are a healthy thing for communities. Hudson won her primary in 2019 against former city councilor Kathy Galvin.

Deeds and Hudson have themselves a competitive primary. However it plays out in the 11th District, across the state, with dozens of legislators retiring from the capitol and others facing competitive primaries, “It’s a generational election for Virginia,” says Hudson. “It’s tectonic change.”