It’s often said at land use public hearings that there should be more places to live in Albemarle and Charlottesville. Both communities have adopted policies that seek to build thousands of units, and they’re challenged by housing advocates to spend millions a year to help keep them within financial reach of those with lower incomes.

What actually gets built is a combination of what the private sector is willing to risk building and what nonprofit housing developers are able to cobble together. A lot happened in 2022 to help measure progress that may or may not be happening.

This year, Charlottesville City Council successfully fought off a legal challenge against the November 2021 adoption of the Comprehensive Plan, but it will begin in 2023 looking for a new city attorney. There are at least two pending land use lawsuits, and there will likely be others.

Meanwhile, the zoning code is being rewritten to allow every property to have at least three units without further approval from City Council.

Albemarle County is reviewing its land-use rules and regulations now, but most of the conversations on zoning and growth have been in smaller meetings out of the spotlight. At the same time, the school board and parents are warning that classrooms are getting more crowded and new buildings are needed soon.

Toward a denser Charlottesville

Charlottesville’s future zoning code is intended to eliminate the role that public hearings play in the land use process. In 2022, there were several high-profile rezonings and other land use decisions that will add more residential density across the city.

Council approved a special use permit in September that will bring 119 units to 2005 Jefferson Park Ave. A month later, several neighborhoods filed suit. Council also approved a rezoning on around 12 acres in Fry’s Spring off of Stribling Avenue that hinged on Southern Development loaning the money to build a sidewalk on the rural-like urban street. That is the subject of another lawsuit. Will the sidewalk be ready in time?

Council will not likely be directly involved in another development that could end up in court as well because it’s a by-right project. Seven Development filed a plan to build 245 units off of East High Street in three buildings constructed on imported dirt to raise them out of the flood plain. An opposition group has retained counsel to challenge the developer’s contention that the project must be approved if it meets the letter of the city’s technical requirements.

But, for those with means, that may be another avenue to stop development.

One of the plaintiffs in the JPA lawsuit is Jimmy Wright, the CEO of the Jefferson Scholars Foundation. Wright owns a house on Observatory Avenue, but the foundation’s headquarters are located on Maury Avenue. This year, council approved a special use permit for Southern Development to build 64 units. The foundation bought the land for $4.3 million, killing the project.

In the future, all projects could be more like the East High project. A major goal of the zoning rewrite is to eliminate the role City Council plays in deciding these issues. A major question in the 2023 election will be whether that’s really what Charlottesville voters want.

The Affordable Housing Plan adopted in March 2021 calls for council to invest at least $10 million a year in construction of new units. Both the Piedmont Housing Authority and the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority made progress this year toward projects they’ve had funded by the city.

Prep work for the first phase of Friendship Court’s redevelopment transitioned into the first units coming out of the ground. There have been delays in the renovation of CRHA’s Crescent Halls as well as the first new public housing units in a generation. New tenants are expected to move in soon. The public housing agency also tapped into money set aside for rental vouchers to buy three properties that will remain deeply affordable units.

Piedmont Housing Alliance also anticipates public funding for two projects on Park Street for which council made approvals despite arguments from nearby residents that the roadway can’t handle the traffic. Currently no bus routes travel that way. Transit is often seen as a solution to congestion, but route changes that were approved in the summer of 2021 will not go into effect until at least the end of 2023.

No matter how the zoning rewrite ends up, the city has struggled this year to process building permits. There was a two-week pause in accepting new ones in late May. A building official was in place by early September, and this will continue to be an area to watch.

Albemarle County prepares for growth

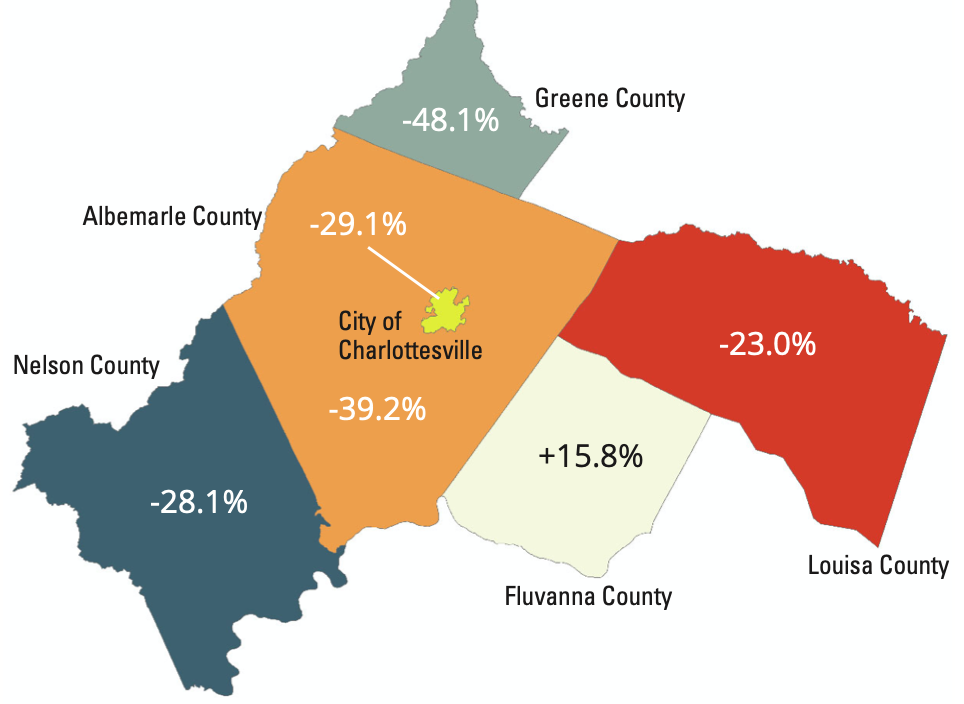

Since 1980, Albemarle has had a growth management policy that directs growth into the 5 percent of its land mass designated for density. The idea is to conserve the rural area and to try to ensure infrastructure in a locality that has grown from 83,532 people in 2000 to an estimated 113,535 in 2021. This policy is getting its first major scrutiny in the first phase of the county’s Comprehensive Plan review that is currently underway.

Since 1980, the build-out for many rezonings has come in below the maximum size allowed. That provides fuel for those who would like to expand the growth area, but others argue the existing areas just need to be bigger. In October, the Planning Commission encouraged the potential developer of one property on U.S. 29 to go higher than five stories. The land is currently the home of C’ville Oriental.

However, the Planning Commission recommended denial in late November of a plan to build 525 units on Old Ivy Road out of a concern that the additional development will overwhelm the two-lane road. The developer will take its chances early next year before the Board of Supervisors. Nearby, the University of Virginia has plans to redevelop Ivy Gardens for over 700 units, but there is no timetable for when that might actually happen.

In November, the Albemarle supervisors approved the second phase of a rezoning for the conversion of Southwood Mobile Home Park to a mixed-income community. The first phase has been under construction on land just outside the original park, and will feature a mix of market-rate and subsidized units. The second phase will add between 557 and 1,000 units, and 227 of them must be below market. The final negotiations hinged on how much Albemarle will have to pay for a potential site for a future school.

University of Virginia continues to acquire properties

This year the first buildings began to come out of the ground at the University of Virginia’s new Emmet-Ivy corridor. The school’s foundation has spent years consolidating properties for a future precinct that will include the School of Data Science, a new hotel and conference center, and the Karsh Institute of Democracy.

But UVA’s appetite for land continues. The property that currently houses Moe’s Original BBQ sold for $2.25 million in late October to an LLC associated with the UVA Foundation. This land across from Davenport Field is next to Foods of All Nations, which the foundation bought for $20 million in late 2021. There are currently no long-term plans for what might happen there.

Another refrain from housing advocates is that the University of Virginia should house more of its students. Darden may do just that with a future master plan.

There was also some progress this year toward UVA’s pledge to work with a development partner to build between 1,000 and 1,500 affordable units in the community. Two out of three sites identified are moving forward, and the next milestone is to send out a formal bid for firms to build the projects on land owned by UVA or the foundation.

UVA effectively increased its influence over land use decisions in Albemarle when two top officials were appointed to the Planning Commission. Luis Carrazana is the associate architect for the University of Virginia and Fred Missel is the director of design and development for the UVA Foundation.

Meanwhile, UVA prepares for the future by agreeing to demolish some of the past. The Board of Visitors approved a plan to take down University Gardens on Emmet Street, citing the high expense of refitting the existing buildings for the 21st century.