The moment you enter Second Street Gallery, you appreciate the variety of techniques featured in “Mirabilia naturae (Wonders of Nature)”—the precise, elegant line of Lara Call Gastinger’s works of paper; the poetic, emotive quality of Giselle Gautreau’s paintings; and the velvety tones and photographic verisimilitude of Elizabeth Perdue’s palladium prints. Each medium and style has its own formal and evocative allure, while also being ideally suited to capture and convey nature, a subject with which these artists are deeply engaged.

The differing approaches work very well in concert throughout the show, and specifically in the grid arrangement of 30 6″x 6″ squares that form a joint, site-specific piece. “We wanted a way to represent a cohesiveness in the show and came up with this idea of one gridded part of the wall that would embody all three of our styles together,” says Gastinger. “We love it. It shows everything from the detailed work of mine to the dreamy photographs of Elizabeth, and then the moody landscapes of Giselle.”

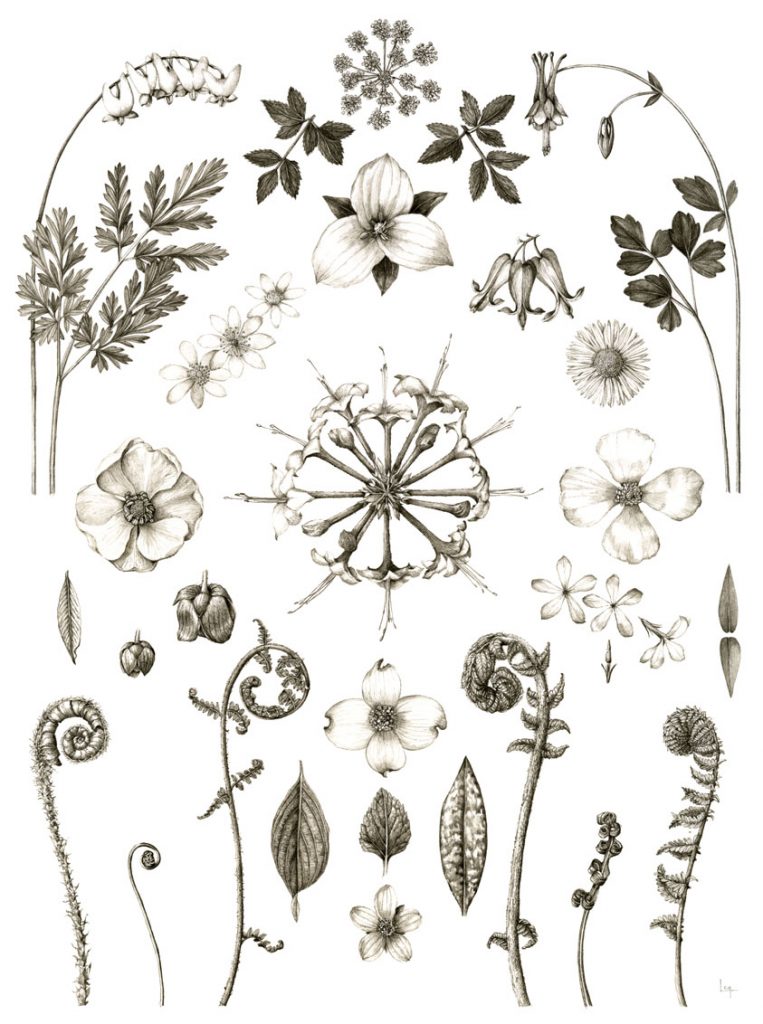

The individual works that make up Gastinger’s “Seeing Plants: A Year in Virginia (January-December),” feature florae as they appear during a given month. Her graphically symmetric arrangement of specimens is derived from the illustrated botanical plates of German scientist Ernst Haeckel. Gastinger uses the dry brush watercolor technique (a small amount of paint—without water—is used with a brush) to produce the extraordinary precision. Just look at her wispy paradise flower in “Seeing Plants,” or the thin hair-like filaments on the fiddlehead fern stems in “Emerging Ferns.” In this and the aforementioned series, Gastinger limits her palette to sepia, which produces varying tones of gray. In other works, she introduces color. Throughout, you marvel at Gastinger’s ability to artfully join scientific veracity with a finely tuned sensitivity to the myriad aesthetic qualities of her subjects.

In her contemplative encaustic paintings, Gautreau uses tonal values to create mood. She downplays detail in these softly edged, atmospheric works, keeping her palette muted and focusing on dusk or twilight when shadows grow and light is diffused. The multiple layers of oil and encaustic that Gautreau employs expand the visual depth while augmenting qualities of luminosity.

In “Virginia Nocturne with Fireflies,” the insects of the title appear as pinpricks of brilliant bluish light against a backdrop of inky conifers. Hazy silvery light from the moon illuminates the sky and shines on a small glade in the foreground, creating the effect of a spotlit stage. Here, a patch of springy clumps of grass with worn areas of dirt is conjured out of lush brushstrokes in vivid green and yellow. A simple composition, the piece evokes childhood memories of the ineffable magic of lightening bugs and moonlight in a summer garden.

“With landscapes, there’s a point where the viewer might connect with them and feel some familiarity with something,” says Gautreau. “But if I get too specific, unless it’s something they have a personal connection to, they lose interest. So, I walk that line between making work that’s rooted in something specific, while also leaving it open to interpretation.”

Palladium printing is an old process, prized for its beautiful effects and archival resilience. Traditionally, large-format cameras are used because the technique requires the negative to be the same size as the image. Perdue uses a Calumet camera with either 8″ x 10″ or 4″ x 5″ negatives. When she’s ready to print, after first processing her film, Perdue paints an emulsion containing palladium salts and a light sensitizer onto watercolor paper. After it dries, she lays the negative on top to make a contact print. She then places this in a light box for exposure, with the addition of a developer. How long it stays in there depends on the desired effect, but it can range anywhere from a few minutes to an hour, or even more.

“I love the tones, the gradations and the grays, and also the texture of the paper. None of it is digital,” says Perdue. “It’s all very tactile—very hands-on. It’s old school. I love that about it.” While palladium printing may be complicated, it’s also simple in the sense that the artist can be involved and in control of the entire process.

Perdue gathers her subject matter on walks, looking for things that “shine in their simplicity.” She selects just one stem or branch to photograph at a time, producing a form of portraiture. “I love celebrating the ephemeral quality of a single bloom, or shoot, and capturing it in a medium that is believed to last for up to a thousand years,” she says.

There’s an unmistakable elegiac quality to “Mirabilia naturae.” We see it in the desiccated magnolia leaf, the fragile fireflies facing collapse, and the somber grandeur of a lone magnolia bloom. It’s easy to revel in each approach, and also in the wonders they present, and it’s very hard to leave the gallery without being more mindful, observant, and appreciative of the ever-fascinating natural world.

Lara Call Gastinger, Giselle Gautreau, and Elizabeth Perdue are featured in “Mirabilia naturae (Wonders of Nature)” at Second Street Gallery through May 19.