As a poet, CAConrad is cosmic, their work unrestrained by the page, poems existing as art objects, ecological elegies, ancient technologies. In 2022, they received the PEN Josephine Miles Award for Poetry as well as the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. We recently interviewed them about their new collection of poems, Listen to the Golden Boomerang Return.

C-VILLE Weekly: This collection is more hopeful when compared to your previous. Given the fact that you began writing this book during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, describe how you cultivate hope in your work and how this has changed over the course of your career.

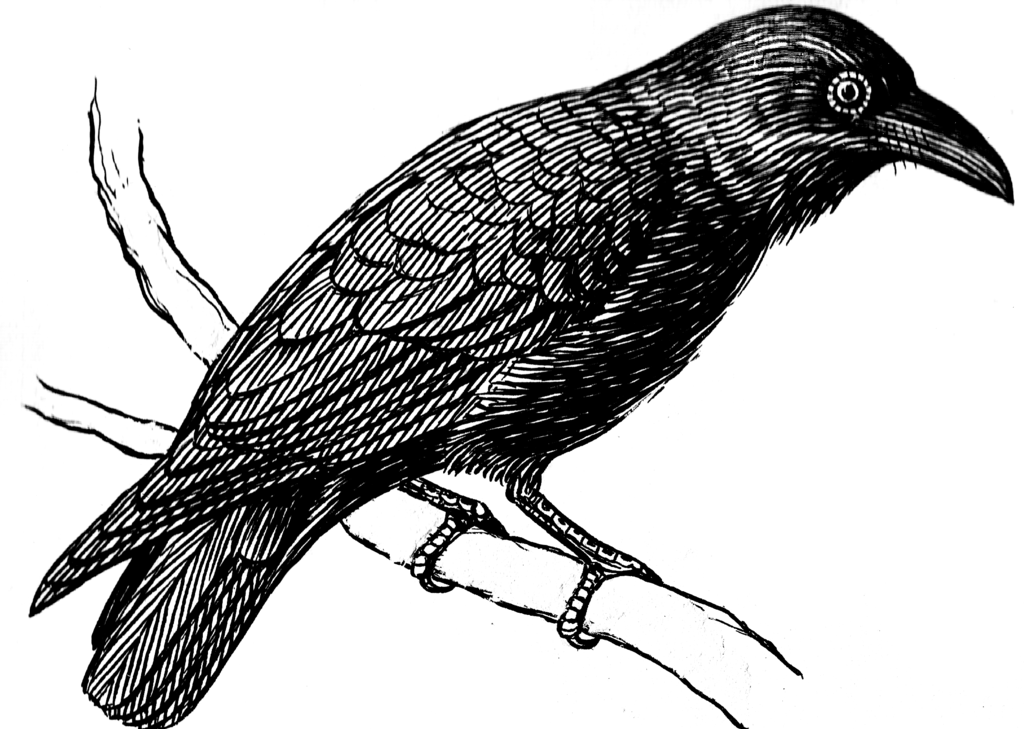

CAConrad: My previous book focused on extinct animals, and when I finished writing it, I realized that I needed to fall in love with the world all over again, but as it is, not as it was. I began writing my new book, Listen to the Golden Boomerang Return, in Seattle, working with crows, who visited me daily during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown for nuts, fruit, and crackers. One of the crows started to bring me gifts, and the new book has a photo of the gifts.

I also worked with coyotes in Joshua Tree, rats and pigeons in Rome, Italy, and squirrels and woodchucks in Massachusetts; animals thriving in our very polluted human world. COVID-19 made me think of the many loved ones who died of AIDS, and those memories find their way into the poems, but yes, there is much love in this new book. It is a beautiful world, and with whatever time I have left, I want to immerse myself in its beauty.

What went into your decisions about the form and structure of the poems in this new collection?

I don’t decide; I surrender. For thousands of years, poets and other artists have told us how they worked with spirits and ghosts, also known as muses. I believe they are real, and they whisper my lines of poetry into my ears. Whenever we think we are being ‘intuitive,’ it is because we are listening to our spirit guides.

From 1975 to 2005, my poems were almost exclusively on the left margin, but when I began using (Soma)tic poetry rituals in 2005, I would feel like throwing up when finishing the poem on the page. I would walk away from it and feel better, but when I returned, I felt like vomiting again. Soon enough, I began “intuitively” moving the lines off of the left margin, and I no longer felt sick, and from that day forward, I surrendered to the process. We work together better with our spirits when we acknowledge their presence. Frankly, I love not knowing what the poems will look like.

You write that the title of the new book “comes from a poem, and the poem comes from a dream.” Describe the role of dreams and other mysterious forces—like numerology—in your life and your writing.

If we look at the number 9, we see its force moving up the stem and circulating in the crown. 9 represents realization or epiphany. All numbers multiplied into 9 heal back into 9, for instance, 2×9=18, and 1+8=9. 3×9=27, and 2+7=9, so it goes: 45, 54, 63, 72, etc. I always write with the number 9, and Listen to the Golden Boomerang was supposed to have 72 poems. Before handing in the manuscript to my publisher, I discovered that I had accidentally written 73 poems, so I tore one and fed its pieces to other poems. The night after doing this, I had a dream that I came home to find some of my new poems having sex on my bed, and when they saw me, they were angry and began shooting letters at me like bullets or arrows. The following day, when I woke, I realized that the poems having sex on my bed were the ones I fed the pieces of the extra poem to. This message was upsetting as if the torn poem was angry, but there are 72 poems in the book.

You’ve also had your poetry shared through public art installations in Greece as well as in galleries and museums around the world. When you think of the multiple ways that people might engage with your work, is there a shared aspect of what you hope they’ll experience through it?

I’m very grateful to have my poems published and also to have them installed in galleries as art. After my event for the New Dominion Bookshop, I will drive to Tucson, where I will install my newest show at [the Museum of Contemporary Art]. I trust the audience, so I never think about their experience. I overwrote my poems when I was younger because I wanted to be sure the reader understood exactly what I meant, and I’m grateful that I soon realized how impossible that was.

Each human being is unique because our experiences cultivate us and shape the lens through which we view the world, meaning no one will ever understand exactly what I mean in my poems. Once I realized this, it was liberating! I no longer had to think about the audience because I could trust them to understand my poems on their terms. A thousand different people reading one of my poems will translate it into a thousand new poems, which is a beautiful gift back to the poet.