As the University of Virginia looks to build a $100 million biotechnology institute at the Fontaine Research Park, Riverbend Development has filed its latest plan for a 69-acre parcel of land that appears rural, but is very much in Albemarle’s development area.

The undeveloped Granger property is between Interstate 64 and the Norfolk Southern railroad tracks. Several previous plans for the property have been filed in the past, but one obstacle has been the cost of a proposed roadway to support regional connectivity.

Albemarle County’s Comprehensive Plan designates portions of the land as Neighborhood Density Residential, which means up to six units per acre on the property.

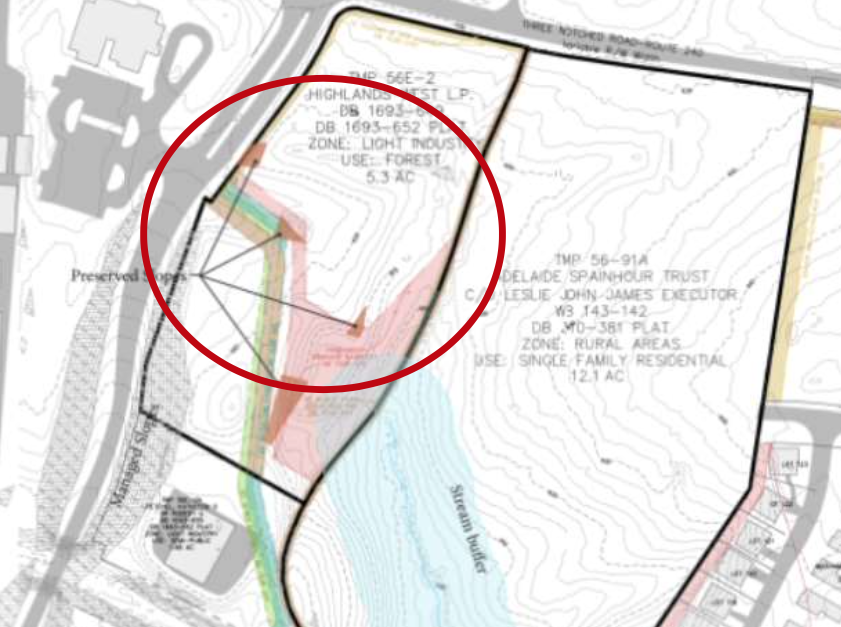

Riverbend wants to build 200 homes, a mixture of townhouses and single-family homes that would be connected to regional trails. A rezoning from R-1 to Planned Residential Development is required to increase the allowed density. Half of the land would remain green space.

“A proposed greenway and trailway connections are proposed through the stream buffer portion of the property,” reads the narrative. “Residents will have convenient access to all of the amenities and resources in the area, including options to walk or bike to Charlottesville and UVA.”

Vehicular access to the site is currently only possible through Stribling Avenue, a street that runs through the Fry’s Spring neighborhood before becoming a one-lane road that connects to Fontaine Avenue. This proposal avoids using that roadway for vehicles.

Instead, all motorized vehicles for this planned development would use an entrance onto Sunset Avenue Extended. The proposal does not include any upgrades to local roads, nor is there a reference to a project proposed in 2004, a time when Albemarle, Charlottesville, and the University of Virginia had a public body that discussed potential infrastructure projects at public meetings.

The Southern Area B Study commissioned by the now-defunct Planning and Coordination Committee recommended a connector road between Sunset Avenue Extended and the Fontaine Research Park. This potential road was much discussed, but the cost to go either under or over the railroad track was considered too prohibitive.

Nevertheless, Albemarle County still had the Sunset-Fontaine Connector as its No. 11 priority on a 2019 list of potential projects. This roadway is included in the federally mandated long-range transportation plan that was last adopted the same year.

The current plan is at a lesser scale than what has previously been submitted.

In 2005, Riverbend Development submitted a Comprehensive Plan amendment to change the land to Office Service for a mixed-use development with 500,000 square feet of office space and 400 dwelling units. This proposal did depict the roadway.

Riverbend’s most recent plan for this property in the summer 2021 was a subdivision that would have carved out 73 single-family lots. That plan would not have required a rezoning and could have been done by-right.

“The site contains sensitive areas that we felt important to preserve, so we are balancing the density with trails and natural areas,” says Ashley Davies, vice president at Riverbend Development.

A community meeting will eventually be held by the 5th & Avon Community Advisory Committee.