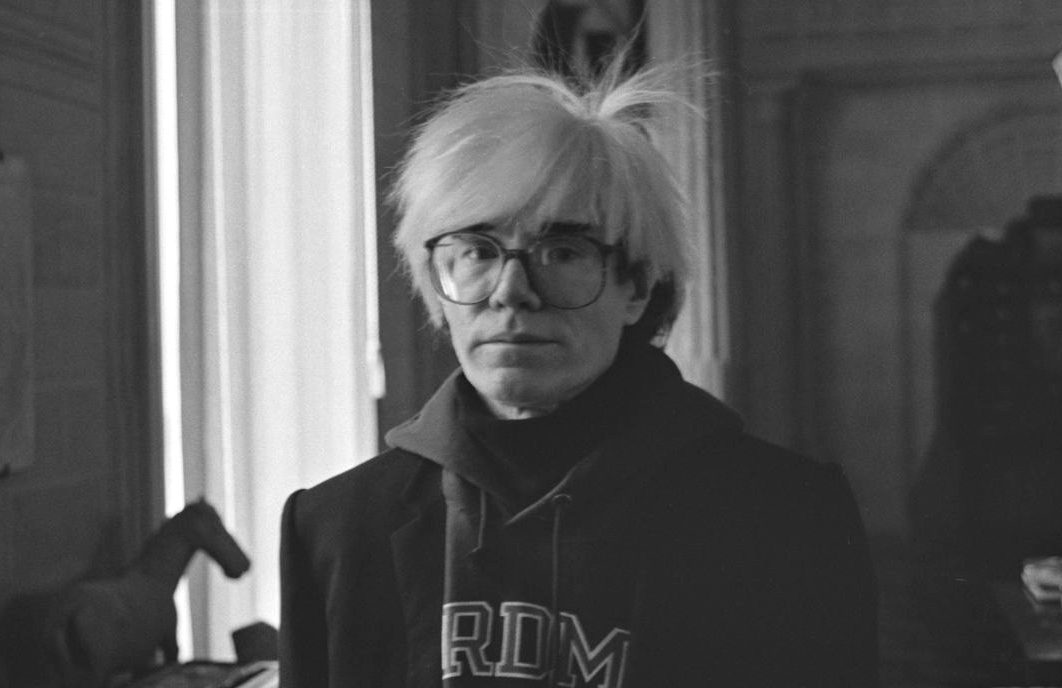

Whether you love or hate Andy Warhol’s work, his impact on the arts as a provocateur, businessman, and impresario is immeasurable. Andrew Rossi’s six-part Netflix series “The Andy Warhol Diaries” sets out to pierce the façade its subject presented to the media. The series gives a fairly nuanced portrait of the godfather of pop art through new and archival interviews with Warhol, his co-workers, friends, and critics. Along the way, it explores Warhol’s era(s) almost as much as it does its subject.

The first three episodes follow Andrew Warhola, Jr. from his early years as an awkward Pittsburgh kid, through his initial New York graphic design career, into his ascension to art superstar, offering fascinating details, like how the Russian Orthodox iconography of his youth influenced his style. The bulk of the story revolves around the period from 1976-1987, when Warhol dictated his activities to writer Pat Hackett. What began as daily accounting by phone became full-fledged diaries, which were published posthumously in 1989.

Therein lies the series’ biggest flaw. Extrapolating on Warhol’s statement “I want to be a machine,” Rossi has an A.I. recreation of the artist’s voice reading his diary entries in a clumsy simulation of his trademark monotone. This synthetic Warhol is gimmicky and off-putting, mispronouncing words robotically like a GPS, and ending its sentences in a clipped, computerized way. The series is clearly attempting to transcend Warhol’s mythic status and humanize him, but this artificial speech undermines a fair amount of those worthwhile efforts. And probably the other biggest problem here is a string of unnecessary dramatizations of Warhol’s private moments, his face always obscured. These precious, stagey vignettes resemble reenactments from an “Unsolved Mysteries” rerun.

That aside, “The Andy Warhol Diaries” is engaging overall. The interviews with his co-workers and others are generally informative, funny, and revealing. Standouts include Interview magazine editor Bob Colacello and director John Waters, who praises Warhol as a trailblazer in underground cinema. In terms of presenting Warhol’s humanness and emotionality, the series is particularly poignant when it examines Warhol’s asexual pose and his secretive romantic life—or lack thereof—with his various companions like Jed Johnson and Jon Gould. And despite the obvious veneration of Warhol, Rossi deserves credit for including quotes from the brilliant art critic Robert Hughes, arguably Warhol’s sternest detractor, who once called him “one of the stupidest people I’ve ever met in my life . . . because he had nothing to say.”

Archival footage of Warhol-era Manhattan and his studio, The Factory, is memorable, including excursions into Studio 54 and the thriving ’70s gay bar scene. The music is well-curated by period, including Sparks’ “The Number One Song in Heaven” and The Skatt Bros.’ “Walk the Night.” But Nat King Cole crooning “Nature Boy” over the opening credits is an odd choice, even if it’s used there ironically.

Was Warhol a ridiculous charlatan or an artistic powerhouse—or both? Was he a deep soul, or, as Truman Capote described him, a “Sphinx without a secret”? “The Andy Warhol Diaries” doesn’t definitively answer questions like these, nor should it be expected to. But it does partially succeed in revealing facets of Warhol that the artist himself seldom, if ever, would.

“The Andy Warhol Diaries”

Six-part series

Streaming (Netflix)