Director Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers is a love letter to 1970s cinema. An avowed cinephile, Payne affectionately evokes the era’s character-driven and frequently dark films with this wry comedy-drama. Payne’s Sideways’ star Paul Giamatti delivers a rich, funny performance in the lead, helping The Holdovers stand out as one of 2023’s best American movies.

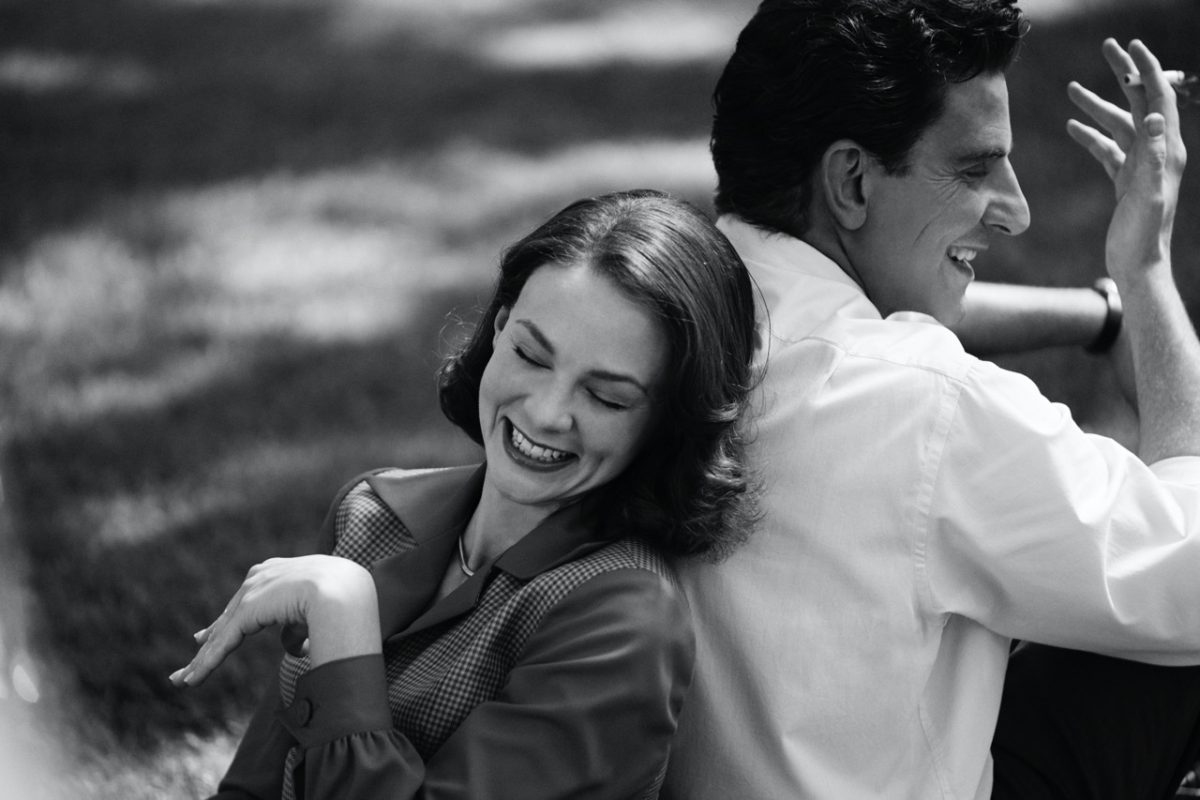

Set in 1970 in an isolated Massachusetts boarding school, the film focuses on curmudgeonly teacher Paul Hunham (Giamatti), who must spend the duration of the Christmas holidays minding five students who are unable to return home. Hunham, a former student himself, has spent most of his life sourly entrenched on the school’s campus. Four of the kids manage to get out, leaving Hunham alone with his witty, troubled student Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) and cafeteria chief Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph). Each of these three disparate people carries their own burden of grief and confusion, and over the holiday season, they gradually bond and enliven their peculiar circumstances.

Screenwriter David Hemingson has created a highly literate script that is by turns funny, touching, nasty, and sweet, without getting treacly. Its humor is akin to Michael Ritchie’s comedies like Smile and The Bad News Bears. The sharp dialogue is peppered with far-ranging cultural references—from the Punic Wars to Artie Shaw—and the filmmakers trust the audience to catch them all. This respect for the viewer’s intelligence makes the movie a welcome change from Hollywood’s tendency to aim for the lowest common denominator.

The Holdovers has been criticized for not delving deeper into its period’s volatile cultural landscape. That the film doesn’t fall into the worn-out clichés usually trotted out in such films—protests, hippies vs. cops, etc.—is a relief. Payne’s focus is on his characters, although there are specific jabs at the Vietnam War’s destructive misguidedness. Also to the film’s credit, Payne deftly manages to simultaneously convey the warmest and the most depressing sides of Christmas.

Without revealing some of The Holdovers’ many intriguing surprises, it’s a story told on a small but intensely detailed canvas that explores the tribulations of teenage life, middle age, the spoiled rich, and the struggling working class. But it’s also about the continuity of life and surviving and thriving in the face of tragedy.

From Giamatti down to the smallest walk-on parts, the cast is well chosen and in excellent form. Giamatti clearly savors playing another of the fussy, fusty oddball roles he excels at, and he’s a joy to watch. First-timer Sessa registers very well as the anxious, wound-up Tully. Randolph’s deadpan reactions to her nerve-wracking companions are wonderful, as are her dynamic moments in emotionally charged scenes.

Working on a modest budget, The Holdovers’ exceptional creative team convincingly recreates vintage New England without belaboring the period details. It looks, feels, and practically smells like 1970, from the ugly furniture, to pipe-smoking in a movie theater, to the W. C. Fields poster on a dorm room wall. Production designer Ryan Warren Smith and costume designer Wendy Chuck have done especially remarkable work.

The Holdovers excels as an ode to ’70s films in countless ways, and perhaps most strongly in its merciful lack of pat, easy answers. It offers the kind of rewarding and emotionally jagged story that has all but vanished from the movies, and it comes highly recommended.

The Holdovers

R, 206 minutes | Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, Regal Stonefield Cinema, Violet Crown Cinema