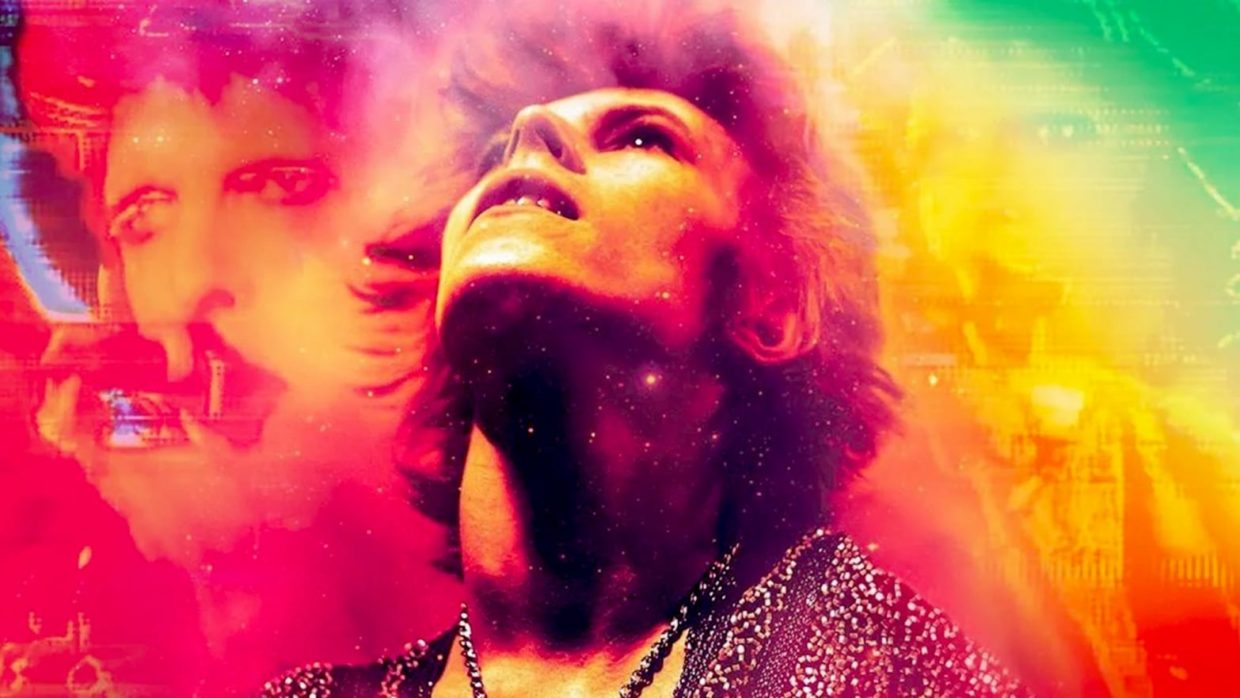

Netflix has elaborately revived Erich Maria Remarque’s classic World War I novel All Quiet on the Western Front, directed by Edward Berger. Remarque’s novel’s descriptions of trench warfare and mechanized bloodshed have lost none of their punch (likewise, Lewis Milestone’s 1930 film version), but in Berger’s take, many elements don’t fully coalesce into the potent anti-war statement the film is intended to be.

German teenager Paul Baumer (Felix Kammerer) and his friends enlist in the Army in a fit of patriotic fervor. Their illusions about war as an exciting adventure vanish as they are thrust into a hellscape of agonizing death. Seasoned soldier “Kat” Katczinsky (Albrecht Shuch) befriends Paul and helps him learn to survive on the front. Meanwhile, in a subplot invented for the film, German diplomats led by Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl) realize their cause is lost, and work toward an armistice with the French.

Most of the movie portrays graphic battlefield violence, offset by occasional interludes of the soldiers at rest. The audience endures nightmarish combat, and some of the battle scenes—especially one involving tanks—are very effective.

The production design, costumes, and makeup effects are all first-rate. The opening sequence is probably the most inventive: uniforms being stripped off freshly dead soldiers, cleaned, patched, and recycled, ready to be handed off to the next batch of doomed youngsters.

All Quiet is pitched in the gory mode of Saving Private Ryan and Fury, but it’s more deeply indebted to Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, the gut-wrenching Russian war film Come and See, and Sam Fuller’s masterworks (one of Fuller’s finest lines from The Steel Helmet is paraphrased here).

Unfortunately, All Quiet plays like a war movie designed to wow people who haven’t seen many war movies, and it suffers most in its character development, pacing, and scoring. Unlike in Remarque’s novel or Milestone’s film, the audience doesn’t really get to know Paul’s friends well enough for their deaths to register. And the film’s soundtrack prominently features an intrusive and anachronistic three-note leitmotif that is jarringly out of place.

The actors are all fine, and deserve more screen time to offset the violence. Key points are also belabored, like the German High Command’s elegant lifestyle juxtaposed with the squalid lives of its soldiers. And an ancient war movie cliché still holds true here: If a soldier shows off pictures of his loved ones, or even discusses them, he’s a goner.

It’s clear just how many antiwar movies are superior to All Quiet in every sense, including the 1930 version, which, despite being over 90 years old, remains better paced and edited.

With the quality of cast, crew, and materials at hand, this adaptation could have been shaped into a more impressive film. All the elements are there—the filmmakers just got carried away with bombarding the audience with horror, and lost sight of the movie’s structure and characters. Yes, war is still hell, but there are limits to which viewers can be bludgeoned with that point.

All Quiet on the Western Front

R, 183 minutes