Director Alex Garland’s tersely titled new horror film, Men, is the kind of movie we need more of: unpredictable, relatively inexpensive, and risky. Garland (Ex Machina) builds a genuine sense of mystery, then pulls off a rare move when he allows the audience to parse the story on its own. Some may argue that his deliberate obscurity goes too far, but Men is a fascinating, gripping, and memorable experience.

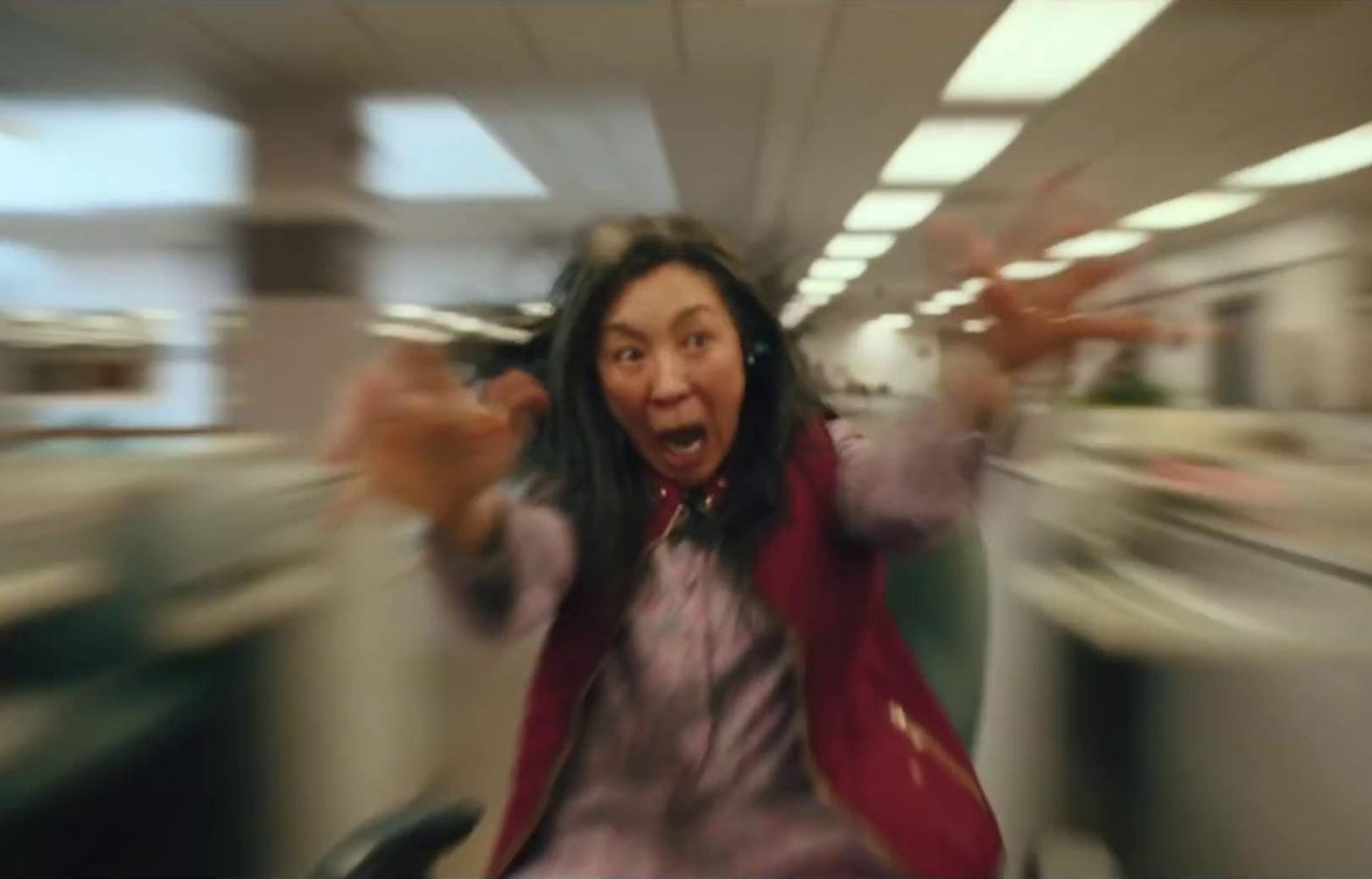

Recent widow Harper Marlowe (Jessie Buckley) retreats to a plush rental house in rural England to heal from her husband James’ (Paapa Essiedu) apparent suicide. Initially enraptured by the estate’s sartorial splendor and the idyllic countryside, things shift quickly toward the bizarre. The locals, all men (all played by Rory Kinnear), are nearly identical—and almost unanimously hostile toward Harper. During a walk in the woods, she is followed by a silent, naked man, and her rustic retreat begins to unravel.

Men is infused with religious symbolism and pagan iconography, beginning with the apple Harper eats upon arriving in this seemingly Edenic setting. (“Forbidden fruit,” her landlord, Geoffrey, jokes.) Her visit to a local church reveals that the cross from its steeple has been cast aside and an altar, adorned with a mythological Green Man and birth imagery, is standing in place of a pulpit. And the film hints at the identical males as expressions of some kind of heathen demigod.

These details position Men firmly in the British tradition of folk horror, where stories involve city people confronted with strange and deadly pagan doings in rustic settings—it is a grandchild of The Wicker Man (1973) and a more obscure gem like Robin Redbreast (1970). The bittersweet song brilliantly bookending Men, Lesley Duncan’s “Love Song,” is the most eerily effective cinematic use of vintage music in ages, and could easily have appeared on The Wicker Man’s unforgettable soundtrack.

Men’s otherworldly plot is grounded by Buckley and Kinnear’s performances. Buckley beautifully conveys Harper’s mercurial emotions, all underpinned by her grief. Kinnear wryly differentiates his many characters—vicar, cop, publican, et al.—imbuing them with a darkly comic edge. This sinister sense of humor is one of Men’s major assets.

Rob Hardy’s excellent cinematography has long phenomenological stretches where the verdant landscape seems like a single, unified organism. Hardy vividly captures the sense of an underlying primeval threat constantly lurking outdoors, treating the scenery as a character unto itself.

People will leave the theater talking about Men. But it loses something in its last act, as it gets loopy, cartoonishly gory, and, at times, nearly indecipherable. When done just right, ambiguous endings are fantastic, but more clues would have helped this one. Men’s murky commentary on misogyny and patriarchal attitudes could also do with clarification. Still, it’s a film that deserves to be seen. One intriguing, imperfect movie is worth a hundred tedious, neatly packaged blockbusters.

Men

R, 140 minutes

Regal Stonefield IMAX, Violet Crown Cinema