With the series of paintings that make up Kristopher Castle’s engaging show “Curriculum Vitae” at Phaeton Gallery, the artist explores Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village and his innovative ideas for education. As the title suggests, the exploration is not a discourse on the UVA founder’s achievements, but rather the artist’s deeply personal relationship to Jefferson’s ideals and his university.

Quorum Pars Fui (“Of which I was also a part”) pays homage to that. In the work, a disembodied hand, Castle’s own, holds the end of a diaphanous ribbon that weaves through the colonnade that runs along the top of UVA’s Lambeth Field. A metaphor for Castle’s life, the fabric references his close ties not only to Lambeth, where he spent the summer of 2001 working at UVA’s costume shop during the Heritage Repertory Theatre’s season, but also, the larger university and Jefferson himself. That summer was a seminal experience for Castle, introducing him to Jefferson and his university, and charting the course that would eventually lead Castle back to the area to live.

Initius (“Commencement”) revisits the fabric of life motif. Here, the fabric’s tail can be seen at the far end of the colonnade that runs along the side at the base of the Rotunda. It’s fluttering away from us, about to leave the Academical Village to commence its existence outside those hallowed walls.

Ab Eo Libertas A Quo Spiritus (“The spirit comes from him from whom liberty comes”) updates the seated statue of Jefferson from the west side of the South Lawn, so that he is shown having just broken a tiki torch across his knee. The allusion is to the assault on the university that occurred in 2017, when protesters wielded these hitherto benign objects in an action that recalled Nazi Germany’s torch-lit parades, albeit with a Walmart touch. Jefferson’s left foot rests on volumes of Locke, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, all major figures of the Enlightenment. This movement, so influential to Jefferson (and other founding thinkers like Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and John Adams), featured rationality and knowledge as its basic tenets.

Castle performs a similar treatment on George Washington in his version of the statue that sits on the east side of the Lawn. Exitus Acto Probat (“The outcome is the test of the act”) depicts Washington covering the Washington Monument, a phallic symbol representing the American patriarchy, with his cape. Castle places tomes by Foucault, Derrida, and Marx—all of whom, according to Castle, would “celebrate [a] critical and punitive reevaluation of [Washington’s] efforts”—at the base of the statue. They are teetering precariously, held in place by Washington’s cane, suggesting he is tolerating them despite their criticism. With this iconography, Castle reminds us of Washington’s integrity. Committed to the freedoms laid out in the First Amendment (freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the right to protest peacefully and petition the government), Washington led selflessly—twice renouncing absolute power. These are important considerations in both assessing Washington’s record, as well as the current events surrounding the 2020 election and January 6.

Inexplicabilis Libertas (“Illimitable freedom of the human mind”) alludes specifically to Jefferson’s vision for his institution of higher learning. For Jefferson, the expansive vista of the Blue Ridge Mountains, once visible beyond the south end of the Lawn, was a tangible representation of the illimitable freedom of the human mind, which is why his original plan kept the area opposite the Rotunda open. It remained this way until Old Cabell Hall, designed by Stanford White in 1898, was erected. Castle paints the building as a transparent ghost of itself through which we can see the view Jefferson always wanted us to see. The nocturnal scene also includes Castle as a young man, exercising his own form of illimitable freedom in the form of streaking the Lawn, a time-honored tradition at UVA.

Omnium Curriculum Gatherum (“Gather all the history”) is arguably the apotheosis of the show. A quintych composed of five panels, the work gives Castle plenty of room to depict Jefferson’s vision for the Academical Village made manifest in both its educational and physical forms. In his rendering, Castle makes it clear that his vision is not sealed in amber, but is changing and flourishing—a fundamentally viable and timeless approach to education and society that has bent, adjusted, and endured.

Castle has a great time conjuring Jefferson’s original course curriculum (anatomy and medicine, fine arts, ethics and grammar, modern languages, zoology and botany, ancient languages, physio-mathematics, history and government, pure mathematics, natural philosophy, and law) with a diverse cast of human counterparts dressed in modern clothes. Castle’s professional experience as a costume designer comes in handy here in his selection of clothing and accessories that identify the various disciplines represented. His admiration for Jefferson’s architecture is evident in his detailed rendering of the Rotunda and pavilions I-IV, which feature respectively the Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Doric (again) architectural orders used by Jefferson with the intention of educating and elevating the student body. In the painting, the pavilions appear left to right: III, I, II, IV.

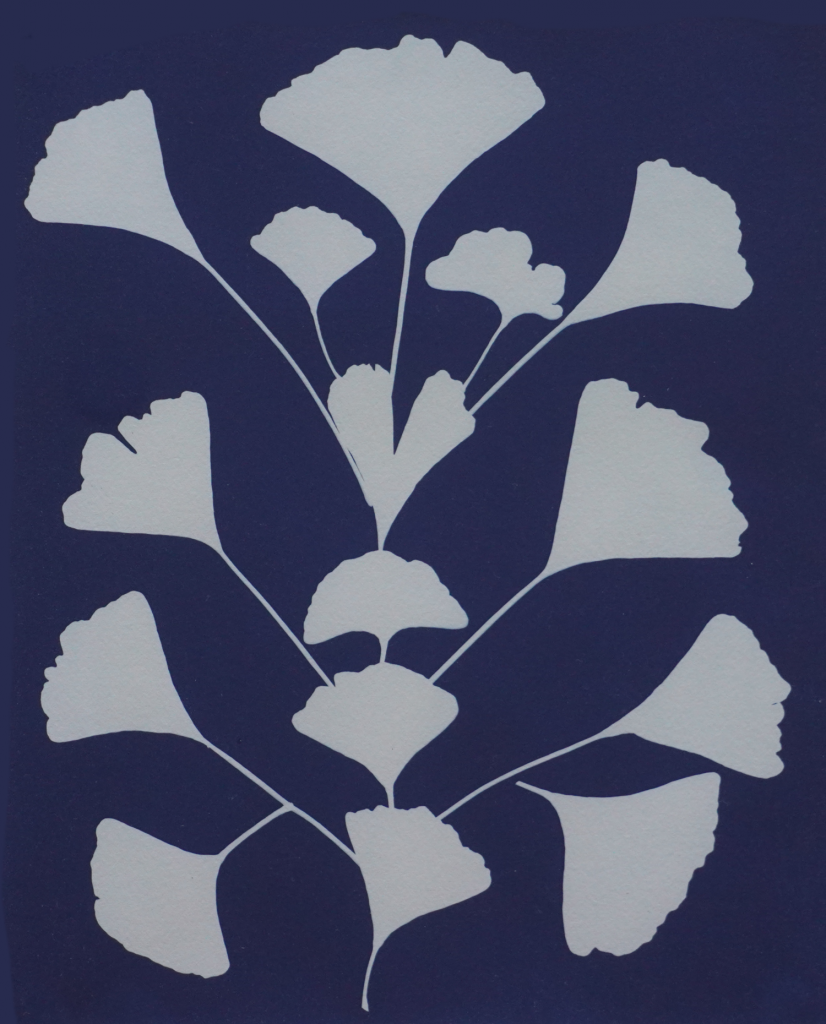

Rounding out the show are Castle’s riffs on the secret society emblems seen on various surfaces around Grounds. These delightful trompe l’oeil works of writing on brick play with the original symbols turning the esoteric into the often amusing contemporary reference.