The spread of COVID-19 across the globe has left no part of our lives untouched, not the least of which is our viewing habits. Streaming services have gone from content delivery platforms to public services as we discover that self-quarantining can result in lots of time to finally whittle down our watchlists.

Everyone’s viewing needs differ at a time like this. Some escape to sci-fi and fantasy, or the comfort of a romantic comedy. Others find catharsis by leaning in with films like Contagion, The Omega Man, or even 28 Days Later. Perhaps now is the time to binge those shows you keep hearing about but never committed to, like “Justified” or “Atlanta.”

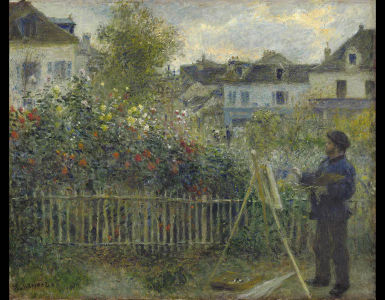

Roger Ebert called films “machines that generate empathy,” and it’s in that capacity that we might find comfort in movies that depict hardship, or taken one step further, were created or exhibited during times of national distress. In viewing, we are not celebrating or finding entertainment value in suffering. If you’re feeling trapped, pessimistic, or paranoid, discovering a film that captures those negative emotions can be calming. These films can serve as reminders that even during the worst events in history, there were people who inherited the world left for them. Cinema is one of the greatest ways we have to pass our experiences to future generations and to connect with generations past.

It was less than a year after the end of World War II before Italian filmmakers tried to reconcile their experience with fascism. Though escapist cinema was initially popular, Roberto Rossini’s Rome, Open City set the stage for a new era of Italian filmmaking. It follows the lives of people in the dwindling days of the war, including a pregnant mother, a resistance fighter, a cabaret performer, and a bumbling but ultimately noble Catholic priest. Production began in 1945, months after the Germans withdrew from Italy, and it was released the same year. The nation’s infrastructure had not been rebuilt, and the film industry had yet to reestablish itself after a period of no money and no resources, yet the movie had the artistry of a film with 10 times its budget. The roughness in its production value only contributes to its beauty; there is always love, hope, and humanity in the world, even in the darkest of times. Other films that use the devastation from WWII as settings include Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, also set in Rome, and Carol Reed’s The Third Man, set in Austria.

Filmed in the middle of the Iraq War, the documentary Heavy Metal in Baghdad follows Iraqi heavy metal band Acrassicauda, as its members attempt to stay creative and stay alive amidst the destruction. Formed in 2000, during the regime of Saddam Hussein, Acrassicauda always faced an uphill battle to be heard and understood. The band was featured in Vice magazine, and in 2006, Vice returned to Baghdad to see how the band was faring following the ouster of Hussein. The situation was grim and only getting worse; the Iraqi insurgency became a civil war, and the band’s mission to gain an audience became a struggle to survive. The chaos of destruction and the risk of death lurks around every corner, as Acrassicauda rehearses in bombed-out spaces and gives interviews in front of collapsed buildings.

The film shows that the need to create is not optional. Art is not a luxury, it is a coping mechanism, and a crucial component of life. (Acrassicauda eventually fled to Syria, then settled in Richmond, Virginia, before relocating to Brooklyn. Its EP Only the Dead See the End of the War was produced by Alex Skolnick of Testament, and the band released its full-length album Gilgamesh in 2015.)

Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is known as a classic satire of the Cold War era. As a glimpse into another time, it is both a riotous comedy and an effective political thriller, with Peter Sellers at his best in each of his three roles. What modern audiences might not realize is just how tense the moment was in which it was produced.

The film began as an adaptation of Peter George’s Red Alert, originally titled Two Hours to Doom. George’s novel is serious in its treatment of the subject matter and does not feature the titular character. While working on the screenplay, Kubrick began to see the idea of mutually assured destruction as absurd, and referred to his adaptation as a “nightmare comedy.”

The first cut of the film ended in a pie fight (this scene is lost to history, but a few stills remain), and features the line “Gentlemen! Our gallant young president has been struck down in his prime!”—which would have been seen by the first test audience, if that screening were not scheduled for November 22, 1964, the day President John Kennedy was assassinated. The film is a masterpiece as it is, but it is worth remembering how necessary it was. The ballooning arms race needed popping, and who better than a clown to do it.

For many, direct confrontation of anxiety through art is the perfect cure for jittery nerves, like caffeine before a nap. But it’s just fine if this sort of film experience is not what you’re looking for right now—and don’t listen to anyone who tells you otherwise. Do what you need to do, enjoy what you like, and stay safe out there. When this is all over, we’ll see you at the movies.